Full Article on The Guardian Website here.

Inquiry into the Stardust inferno in north Dublin, that killed 48 and injured 214, recognises the suffering and grief of those left behind

Deirdre Dames was 18 and on the dancefloor of the Stardust nightclub in the early hours of Valentine’s Day in 1981 when the music stopped and the DJ announced there was a fire and people should head for the exits.

“Then there was a bang and the lights went out,” Dames recalled. “I was trying to make my way to my friends but everyone was pushing and shouting. I got on my hands and knees and crawled to the toilet.”

Scorching heat and black smoke filled the bathroom so Dames, unable to breathe or swallow, stuck her head in a toilet bowl. Whenever she raised her head, all she could hear were screams.

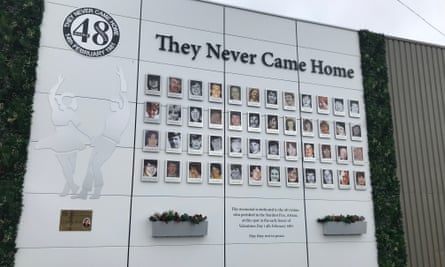

The Stardust inferno in the north Dublin suburb of Artane was one of the worst disasters in the history of the Irish state – a conflagration that killed 48 people and injured 214, many of them teenagers, and raised a host of questions. What caused the fire? How did it spread so quickly? Why were some exits apparently locked?

More than four decades later, survivors and relatives of the dead feel they are finally getting answers – and recognition of their suffering and grief.

Since April, a Dublin district coroner’s court inquest has heard testimony from dozens of witnesses – survivors, bouncers, nightclub managers, emergency crews – in a fresh attempt to find out what happened. It sits with a jury at the Pillar Room of the Rotunda hospital and is expected to conclude in early 2024 after hearing from forensic experts.

“They’re listening to us. That’s a big step,” said Siobhán Kearney, 60, whose 18-year-old brother Liam died in the tragedy. “We’re looking for truth and justice. This has had ripple effects across the generations. It changed everyone’s life for ever.”

Families say previous efforts, including a tribunal of inquiry, a victim compensation tribunal and two legislature-appointed reviews, were rushed, perfunctory or botched, reflecting official indifference to working-class north Dublin communities.

“It’s as if their lives mattered less because it happened in Artane, not Donnybrook,” said Lorraine Keegan, citing a wealthy south Dublin suburb. “Governments pushed it under the table; they didn’t want to know.”

Officials reject that allegation.

Keegan’s sister, Antoinette, and their late mother, Christine, drove the long campaign for an inquest, staging marches and protests until the attorney general agreed. Time had not healed wounds, said Keegan, who lost her sisters Martina, 16, and Mary, 19, in the blaze. “You especially feel it at Christmas and birthdays.”

More than 800 people were in the Stardust in the early morning of 14 February 1981 when it hosted a dancing competition. The fire was first seen in the ballroom at about 1.40am on seats in a sectioned-off area known as the west alcove. Flames ripped through walls and the roof, and engulfed the nightclub within 10 minutes. Witnesses said some exit doors were obstructed or locked with chains and padlocks.

A tribunal of inquiry that convened within three weeks of the fire found there was no evidence about its origin but that the “probable cause” was arson. The finding outraged families because it allowed the nightclub manager, Eamon Butterly, to claim £580,000 compensation for malicious damage, despite the tribunal deeming him culpable of “recklessly dangerous practice”.

The finding of arson, according to families, also besmirched victims. The finding was removed from the public record in 2009, but for Kearney only a fresh inquest could absolve those who died. Her brother Liam survived for a month before succumbing to horrific injuries, an ordeal that scarred the entire family, she said. “His hands had melted. He had no lungs left.”

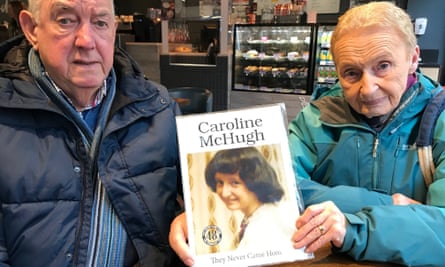

For parents like Philomena and Maurice McHugh, both 84, the inquest has been an opportunity to remind Ireland what was lost. Their only child, Caroline, 17, loved maths, Irish dancing, singing and her CB radio, they said. “She was a funny kid and made friends easily,” said Maurice.

Mortuary officials advised them to not view the body because there was only a torso. “They gave me a piece of her jeans with the comb melted into the pocket,” said Philomena. “Caroline always had a comb. She had great hair.”

The inquest hearings have been harrowing, and at times contentious. “I don’t believe the doors were locked, sir, and that is my evidence,” Butterly told Des Fahy, a barrister for the families, in October.

That infuriated survivors, but all those interviewed for this article expressed confidence in Darragh Mackin, a Belfast-based solicitor leading their legal team, and in the eventual outcome, which could include a finding of unlawful killing.

Dames, who found refuge in the toilet while others died, said she had since suffered depression. “I didn’t want to be in the world. I still have the nightmares,” she said. At the inquest, she met for the first time the firefighter who carried her out. “I got to hug him. It was like winning the Lotto just to thank that man.”